AmericaHypothesis: As much as the Progressive Era established the ground work, the basis of our culture in the 2020s comes, both good and bad, grew out of formations established in the 1920s.

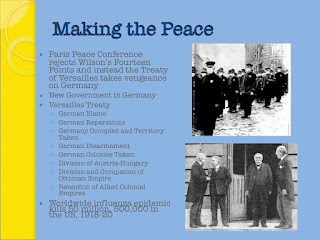

Paris Peace Conference saw to that. Instead of adopting Wilson’s plan for peace without victor or vanquished, the Allies took vengeance on Germany and the Central Powers. The New Government in Germany was forced through the disarmament of the Armistice agreement to accept a Versailles Treaty that beat the Germans even more than what had occurred on the battlefield – and that beating at the end of the war had been pretty bad.

World War I, a product of centuries of Archaic principle, was over and a brave new world lay ahead. The War had killed millions of people and cost massive material and financial resources. It represented the worst of human civilization, a civilization that had loved war and its pomp and glory, and believed in kicking the enemy when it was down. The

Germany had to accept blame for the war, pay massive reparations (actuaries calculated the final price-tag down to the last bullet and life and stitch of cloth). Parts of Germany were occupied and Alsace-Lorraine, most of which was culturally German and had been taken at the formation of the German Empire in 1871 after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, was ceded to France. French revenge demanded German disarmament, the taking of its colonies – its utter humiliation. The French Commander and Chief either boasted or forewarned that peace had been achieved for 20 years. But the populations of Europe were not ready to go back to business as usual and bowing and scraping to a defining ruling class. Gone would be the sacrosanct traditions, and strict formality represented by the ruling houses that took the world in war. A new age would rise, not quite the People’s Revolution as in Bolshevik Russia, but a step towards empowerment of people born out of the ruling class elite.

And to start off the Age? A Pandemic!

Art had been changing in the since the age of Democratic Revolution and the dawn of the industrial era, but it went nuts in the 20s in breaking with tradition. Artistic style and trends indicated by Dadaism, Bauhaus and other forms showed that artists wanted to move beyond the tropes that catered to their rich clients and satisfy the impulses of their artistic minds. Dada meant nothing, and the artistic movement attempted to highlight nonsense in a world that had just gone mad. Surrealism, cubism and other forms showed the disconnect between the horrors of reality and the pursuit of what ought to be – or maybe just the distortion that is life. American artists didn’t go as far afield, at least not at this point, but had been moving towards themes of the significance of everyday life and everyday people – like with Ashcan school of artist, namely George Bellows – he painted a lot of boxing matches, the stuff of the most common, working class people – instead of portaits and landscapes for and of the wealthy ruling elite.

For the first time since its founding in 1789, the United States was a world power. The leading economy in the world relatively untouched by the waste of war, America now proved its martial skill, and diplomatic influence. US culture, movies, art, literature – consumer products – was fast becoming what the world emulated and desired, and yet, the United States wanted no part of world leadership. Politicians and the population retreated behind the two oceans into isolation. The United States did not join the League of Nations and instead of reaching out to a wounded world, cut open immigration through government act in 1920 and 1924 that severely limited who could come to America. Afterall, look what the world had done! World War I was their war, and the pandemic came from them. Keep them out and build a wall – metaphorically at least.

1917 had brought the first Communist government into existence – a direct challenge to corporate control in America. So the government engaged in destroying organizations and individuals who leaned a little too far left. A fear of socialism of any kind came into existence, a paranoia of all things red (which is odd that the Republican Party is associated with Red States?). As had been US practice since the Founding, the United States reduced its huge military raised during the war, down to a minimal force – a good sized navy was kept in place. In fact about the only major international accomplishment of the Federal Government was the signing of the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 with 16 other nations (eventually 31) that basically outlawed war as an instrument of national policy. Of course this was in keeping with the ideals of the American corporate driven empire since its dawn in the late 1800, but now such a policy served its paranoid and isolationist impulses. But the new American empire wasn’t based on what the institutions of government did, it was based on cultural might, and ideas of freedom – oh, and corporate raiding of the global economy, as well.

American writers, many of which were known as the Lost Generation, made American Literature a light in all the world. Fitzgerald, Hemingway and Gertrude Stein helped to articulate and define the mood of the decade.

More significantly, American art was becoming multi-cultural and what was “American” was seen by the world as not merely being produced by a homogeneous white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant population. The Harlem Renaissance flowered by the 1920s and helped to define “American” art, literature and music as inclusive of its African descended population. It’s certainly not that poets, like Langston Hughes, were read, or even known, in every household, but they were read, and read outside of black America. Harlem Renaissance leader, James Weldon Johnson, a classical composer, encouraged high artistic achievement as a means to breading down race barriers and proving the worth of African Americans to European Americans who maintained an exclusive dominance on American political, economic and social institutions. Johnson is often pegged as an elitist who frowned on black working class habits and customs. He preferred Paul Robeson singing Opera to the countless new black artists developing the new language and expression of Jazz. Hughes noted the contradiction of denigrating common black life in his master work The Weary Blues (1926). The poem notes attitudes of an emerging black elite and their desire for cultural distancing – thinking that will abate the racism inherent in American culture. For Hughes, however, Jazz was an expression of what historian Joyce Goldberg called, “Black musical genius!” Music, historically, had been one of the few areas in which the White system had allowed for Black expression and in the 1920s Jazz became God, or culturally close to it.

Jazz became the background music in a rising Urban Culture that was overtaking the 19th century rural ideal of the American ethos. This was the first generation to go to the movies, at least the way we think of it, to listen to the radio, music, comedy, news, commercials – youtube from a box without pictures. While rural America tried to fight back through national legislation like the Volstead Act which enforced the 18th Amendment prohibiting alcohol, Urban America rebelled with illegal clubs, dance hall, and hidden saloons. The Speakeasy was a place to get what a world sick of convention, sick of war, sick of influenza – drugs, sex and wild music. You know, fun!

Urban America came to represent to rural America decadence, immorality and sin – and no, not everyone lived in a barrel of gin, smoking reefer and having sex, probably most did not – but it became the accepted, normal way of life in most cities. A sexual and sensual Revolution had dawned, self-definition and self-determination in ways to make the Puritan of old blush.

Consumer Culture of conspicuous, and often over, consumption.

The new Urban ideal, which is still America today, was a consumer ideal, an attitude of getting and spending, and working to spend some more. This is the their ideal, this is our ideal, this is America to the rest of the world, A

While much of rural America still scratched much of its resources from the naked earth, Urban culture lived off the market. Fueled by Mass Media, which was now possible to market goods in newspapers and radio all around the country, the economy boomed. Incidentally, this was also the decade of mechanization – where machine power overtook muscle power as the main source by which work was done. That only increased the size of the boom. Government helped – giving funds to corporate America to expand its markets, expand its products, expand the ideal that in America you are measured by what you buy. The Smith-Lever Act had earmarked millions of dollars to help corporate America reach more customers and by the 1920s more Americans drove cars, went to the movies, read a newspaper, had an electric you name the appliance, than anywhere else in the world. USA USA USA

And a new cultural ethos, this Urban Cultural Ideal, demanded new gods to reflect the new values.

And the gods came, in the form of “Everyman” … and woman too!

Perhaps the most heralded American at that time, or any time, was Charles Lindbergh who became the first to fly in a plane across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis in 1928. Flying a plane was god-like and even mediocre pilots like Amelia Earhart were seen as superhuman.

For most of American History, sport other than horse racing or polo, or other horsey things, was seen as low-class and unworthy of regard, but the 20s changed that and made sports figures “superstars.” Babe Ruth is the father of the sports icon – Ali, Jordan, all of them owe a debt to the Babe, and to a lesser extent, to the other Babe, Babe Didrickson, who was a female athlete whose multi-sports feats made the ideal of athletics less gender segregated. Less, anyhow.

Movie icons were bigger than at any other time. Hollywood, founded earlier in the 20th century as a Mecca for film, enjoyed a golden age where more Americans went to see movies than in any other decade. And how could they not. Giant screens with giant faces, moving, though not talking, was magical. The general population began their fascination with celebrity, a disease we still have. When movie star Rudolph Valentino suddenly died in 1928 it was purported that several fans committed suicide rather than live in a world without him.

Jazz went from being African American music played mostly in New Orleans and New York, earlier in the century, to a national obsession by the mid-1920s. The ideal of cool and sexy became synonamous with Jazz stars like Josephine Baker and Duke Ellington. Everyone wanted to be just like that … in the Urban ideal, anyhow, but not everyone in the country.

The KKK rose from the dead in the 1920s to become one of the largest organizations in the country. Spurred on by a Trumpian call to stem the tide of change brought by foreigners and brown people, the KKK targeted those of immigrant background who threatened the white Anglo-Saxon, Protestant stranglehold on defining who was, and who was not, American.

For the good and the bad, the 20s defined what life would be in America.

No comments:

Post a Comment